Port resilience is the ability to maintain an acceptable level of service in the face of disruptions (e.g. pandemics, natural disasters and cyber or terrorist attacks); this varies with port size, location and type of operations. Ports' resilience is largely determined by their ability to remain operational and offer services and infrastructure to ships, cargoes, and other customers during disruptions. In some of the existing literature on supply chain resilience, the concept is more narrowly defined to mean the time to recovery (TTR), as also illustrated in figure 2.

A resilient port can cope with shocks, absorb disruptions, quickly recover and restore operations to a level similar to – or even above – a baseline, as well as adapt to changing conditions, as it continues to develop and transform.

Port resilience is linked to the port’s inherent properties as it is a capacity and capability issue, regardless whether there is port activity and traffic. For instance, if a disruption were to impact a port’s hinterland and reduce traffic and cargo flows, the port would be considered resilient if the disruption did not impair its capacity to handle an average traffic level and the corresponding revenue. A port's responsibility is to ensure that it is connected to the global shipping network and its hinterland, and to provide an expected level of infrastructure and services. Factors beyond these realms, such as a disruption at a large manufacturing facility using the port, cannot be effectively and directly addressed by the port. However, given the potential volatility in volumes they should not be considered elements of port resilience, even if they indirectly impact its operations. For example, if a demand surge is created after a manufacturing facility resumes its operations, a port’s capability to handle this surge is considered an element of its resilience. This does not infer that resilience only involves temporary cargo surges; it could also involve a systematic decline in volumes handled by a port, implying the need to adapt to a commercial environment generating less demand, which could be mitigated by adopting relevant measures, e.g. cargo consolidation and the search for new opportunities and markets.

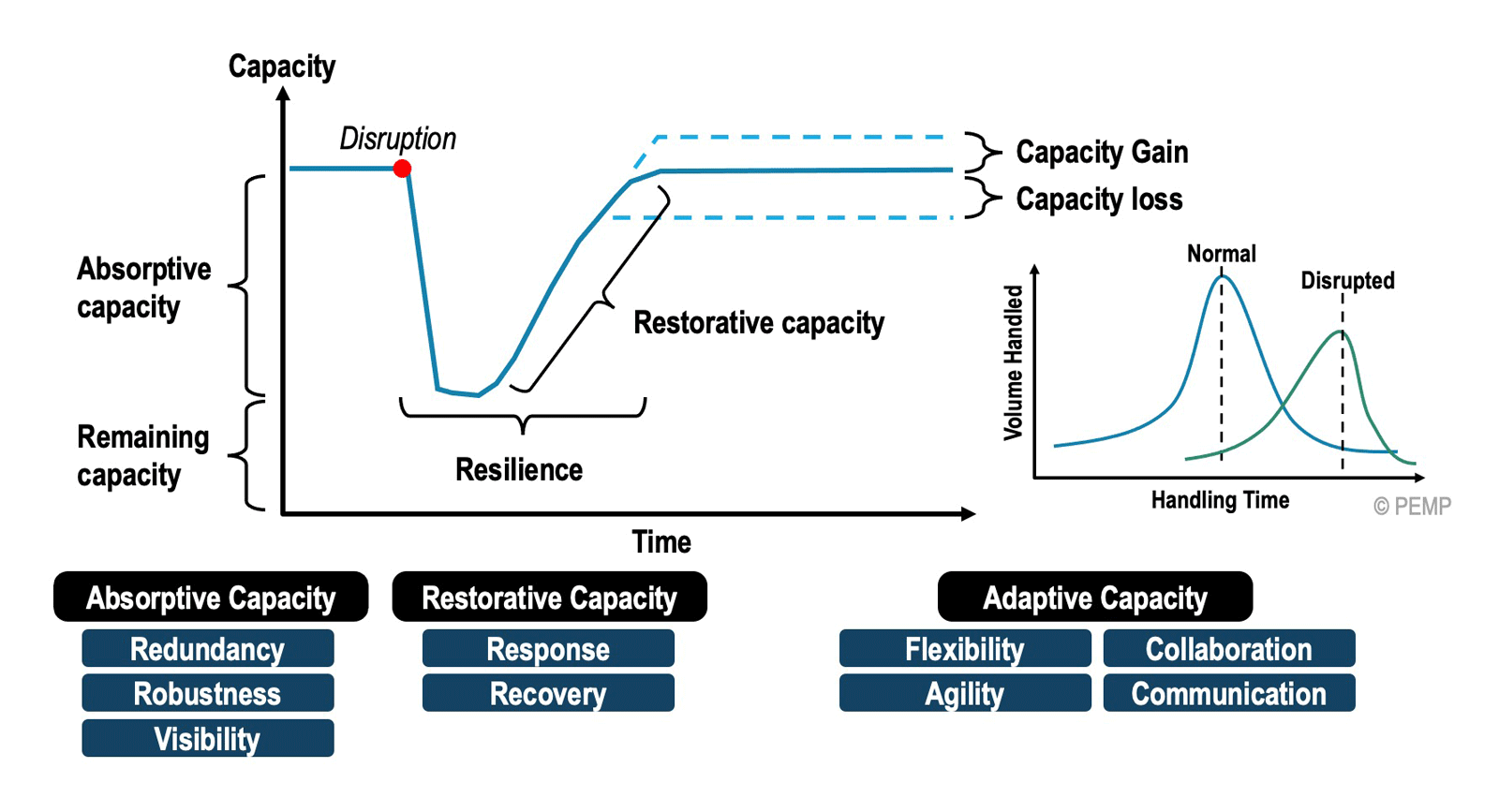

Figure 2: The concept of port resilience

Source: Linkov, I. and J.M. Palma-Oliviera (eds) (2017).

Resilience tests the capacity of ports in three different ways (figure 2):

- Absorptive capacity. The ability of a port or a terminal to absorb a disruption using existing infrastructure and services, while maintaining the same level of service. This implies attributes, such as robustness, redundancy and visibility. A robust system is said not to be impacted by some disruptions as it can withstand them. Ports have technical and engineering design characteristics allowing them to withstand geophysical disruptions, e.g. storms, for which they have a level of robustness. Through “redundancy”, ports are also able to withstand disruptions by being able to accelerate and expand their operations, or by being able to store additional inventory at terminals. Ports have a technical buffer (how much additional throughput they can handle) and a storage buffer (how much extra cargo they can store). Visibility allows port users to access information supporting their operations and make appropriate decisions. Providing real-time information during a disruption reduces any impact on related supply chains as decisions can be taken to defer or divert cargoes.

- Restorative capacity. The ability of a port to recover from a specific disruption to a level of service similar, or even above, a baseline. First is the ability of a port to provide a response to a disruptive event, mainly through its preparedness and the resources that can be mobilized to contain and abate the disruption. Second is the ability of a port to recover and return to a normal operational state with its associated capacity. After recovery, an outcome can be a capacity loss, as recovery leads to lower levels of efficiency. Another possible outcome is that the disruption becomes a "learning event", allowing for a capacity gain and more efficient operations.

- Adaptive capacity. The ability of a port to change its operations and even its management, either in anticipation of, or as a reaction to, a disruption. It involves flexibility, whereby a port can adjust its operations to mitigate disruptions, such as changing its schedule and workflows. A port can also display a level of agility and be able to respond rapidly to disruptions, including having a workforce capable of performing tasks they do not usually perform. Through collaboration, cargo can be routed through different terminals within the same port, or through different ports. If a port is part of a port system with a well-connected hinterland, its adaptive capacity can be improved by temporarily using other ports through collaborative efforts. Lastly, a port can rely on communication to inform stakeholders of the changes they are implementing to allow them to adjust their own operations. A port can also receive and process information from third-party providers, such as carriers.

The most common outcome of a port disruption is a temporary degradation of the cargo handling performance. Under normal circumstances, a terminal (or port) is expected to provide a performance level in which a notable share of the cargo is handled within a designated timeframe. With a disruption, the degradation of the performance can result in substantially longer handling time coupled with a lower capability to handle the traffic. In extreme cases, the disruption is significant enough to force a shutdown of operations. Once operations resume, port labor and equipment must catch up with the accumulated cargo waiting to be handled on both the maritime and inland sides. Other measurable outcomes to port disruption include a loss of revenue and customers. Although a port can have long-term agreements with shipping lines which bind cargo flows, disruptions provide incentives to carriers to reassess their commitments. Auxiliary services and activity clusters gravitating around the port can also be considered, as their performance and activity levels are closely associated with those of the port.

Disruptions can have two types of impacts on ports:

- Operational impacts impair port operations and cause delays, but generally leave port infrastructure and equipment intact. Operational impacts affect all elements of the maritime transport chains with, for instance, ships being delayed, terminals losing revenue, and cargo owners facing inventory shortages. An event, such as a storm, may occur within the port terminal’s design parameters but could nonetheless lead to a slowdown or cessation of port operations. Other notable disruptions can include power outages and labour movements, e.g. strikes. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic impacted port operations by creating labour availability issues due to sanitary measures. However, the most notable impacts were related to disruptions caused by a demand surge resulting from a rapid return in demand for containerized goods, which in turn were boosted by national stimulus policies and support for consumer spending. Several gateway ports and their hinterlands were not able to cope effectively. Yard capacity can be a significant operational constraint, as once a terminal reaches full capacity, it is unable to handle ships effectively. Shipping lines can decide to skip a port call, or alternatively wait until the facility resumes its operations.

- Infrastructure impacts relate to the damage to, or even the destruction of, port infrastructure and equipment. The disruption takes place at a scale above the port’s design parameters. Although some infrastructure and equipment may not have been damaged, those that were damaged would impair regular operations until repaired. Since infrastructure impacts are usually of much longer duration than operational impacts, the port would be impacted by a loss of revenue, reputation and repair costs. These impacts would extend to activities directly dependent on the port that would be forced to find alternatives or to curtail their operations until port activity resumes. Some actors, e.g. shipping lines, have more flexibility as they can allocate their ships to other ports and shipping markets while the disruption endures.

Additional information about Port Resilience is available in PART II of this guidebook.