A risk culture describes the values, beliefs, knowledge, attitudes and understanding about risk shared by a group of people with a common purpose (Institute of Risk Management, 2012). This applies to private companies, public bodies, governments and not-for-profit entities.

Although there is no single method of ‘measuring’ risk culture, several diagnostic tools are available and can be used to assess and track an organization’s risk culture. The mix of tools and the order of their deployment will depend on the organization’s risk management maturity level. The Institute of Risk Management has articulated a Risk Culture Framework around which to analyse, plan and act to influence risk culture within any organization (Institute of Risk Management, 2012).

A port's risk culture determines its ability to balance risk and opportunities as they emerge. An appropriate risk culture ensures that ports recognize the importance of effective risk management, and that their actions are consistent with their operational risk policies, procedures and appetite. Inappropriate risk culture can lead to increased operational risks and amplify impacts.

Risk culture is concerned with risk-taking, as well as risk control. All ports must take risks to achieve their objectives, including having to accept a degree of operational risk exposure. A port's risk culture will influence whether people perceive an operational risk as beneficial (e.g. associated with pursuing a potential opportunity) or a threat. A port can use surveys to gather the views of staff, interviews, or employee panel sessions to ascertain its risk culture. An example of a risk culture questionnaire can be found in Appendix A of the Institute of Operational Risks Risk Culture Guidance. A survey questionnaire alone will not be sufficient to fully capture a port's risk culture; however, the key elements to be addressed as part of this exercise include:

- Whether staff share the risk management objectives outlined in the policy;

- Attitudes towards the risk function or specific operational risk tools and procedures (e.g. HS);

- The presence of subcultures, e.g. differences in responses based on functions and location or levels of seniority;

- Whether staff believe that the port is taking too much or too little risk; and

- Whether staff have adequate knowledge and understanding of risks and risk awareness.

Surveyed staff should represent a port's workforce, with contract and other third-party staff operating in relevant locations across the port also included in the survey. Changing the risk culture takes time and is typically best achieved in small incremental stages. A risk culture should not be measured as a one-off and should be reviewed at least once a year. Several metrics can inform a port's risk culture, such as staff turnover, staff conduct (fall or rise in staff grievances), risk policy compliance, losses and near misses.

Port leaders and managers can influence their ports’ risk culture through the following actions:

- Being visible and consistent in terms of what they say and do. This requires them to act in a way that supports the values of the organization as well as its policies and procedures;

- Sending out clear messages regarding their expectations about risk management and decision-making. Including having a clear risk appetite statement and risk management policy;

- Making it clear that all areas of risk management, including operational risk management, are important value-adding activities, not simply 'cost-centres'; and

- Being open to challenges and avoiding becoming blind to or against new information about their risk exposures and risk management strategy.

Human resources (HR) processes and management techniques can influence a risk culture, including recruitment and performance management approaches. Clear communication channels are required to escalate potential concerns as quickly as possible. Port workers should trust that management listens to their concerns on operational risk and how they are managed. It is important to establish a ‘just’ culture, which encourages open and no-blame reporting, while ensuring that accountability is maintained. The establishment of an effective whistleblowing procedure is also important.

Risk appetite is the amount and type of risk that a port is willing to retain to meet its strategic objective", and mainly involves decision-making. Every action or decision within a port involves an element of risk. Therefore, the port must distinguish between risks that are likely to result in value-creating opportunities, such as profit, a positive reputation and improved services, as opposed to those that may undermine value. By determining an appropriate appetite for risk and implementing a framework to ensure that this appetite is maintained, decision-makers avoid exposing their ports to either too much or too little risk.

The benefits of implementing a framework to determine and manage a port's risk appetite involves, among others:

- Enabling senior management to exercise appropriate oversight and corporate governance by defining the nature and level of risks it considers acceptable (and unacceptable), and setting appropriate boundaries for business activities and behaviours;

- Providing a means of expressing the attitude of senior management towards risks, which can then be communicated throughout the port to help promote a risk-aware culture;

- Establishing a framework for risk decision-making to help determine which risks can be accepted/retained, as opposed those that should be prevented or mitigated;

- Improving the allocation of risk management resources by moving these into sharp focus;

- Helping to prioritize issues, specifically risk exposures or control weaknesses outside a determined "risk appetite or "risk tolerance";

- Ensuring that the cost of risk management does not exceed the benefits; and

- Balancing development/growth/returns and the associated inherent risks.

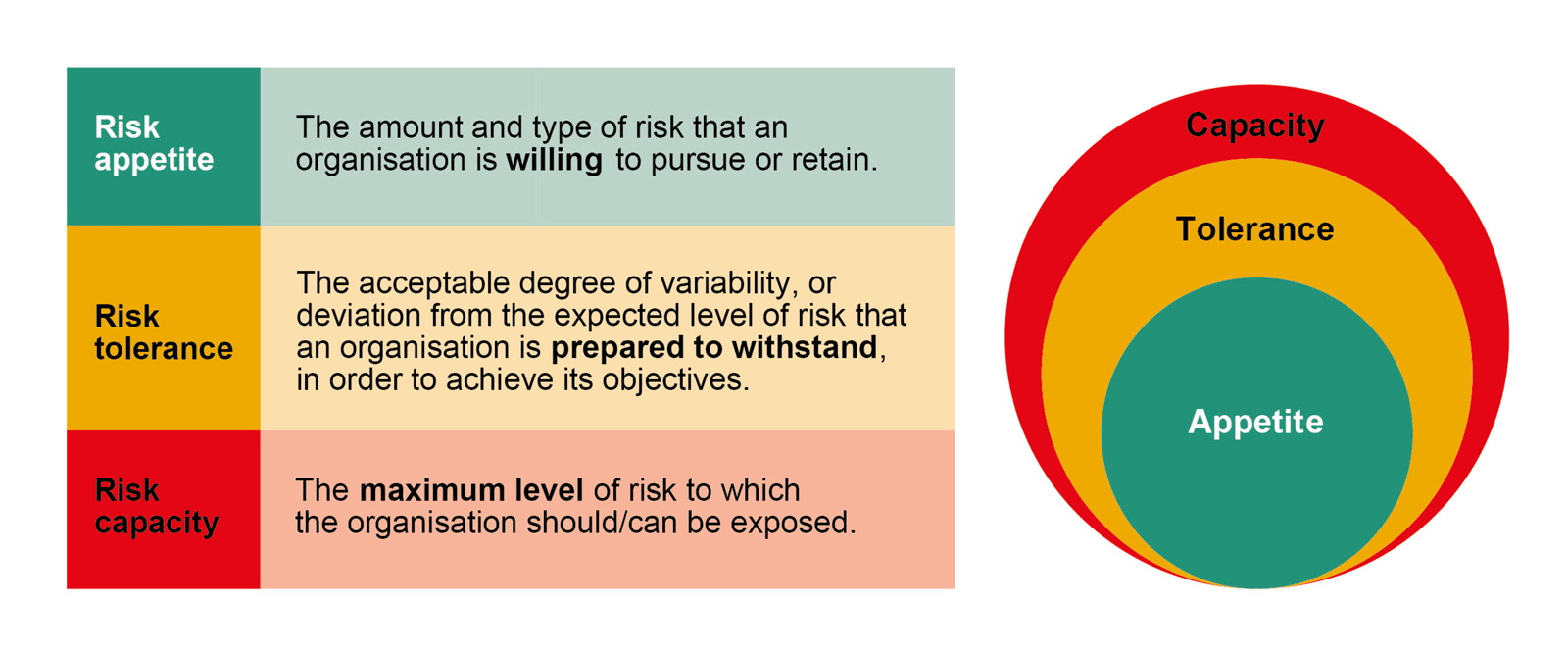

Mainstreaming "risk appetite" in a port requires looking at the "risk tolerance", which is typically used for a specific benchmark for the acceptability of a given risk exposure or metric. In other words, a port may decide that it is prepared to tolerate a particular number of operational errors or control weaknesses because their elimination would not be cost-effective.

Risk tolerance is often expressed by using a colour scale:

- Green: Acceptable and no immediate action required, except for routine monitoring.

- Amber: Tolerable and investigate to verify and understand the underlying causes and consider ways to mitigate within a specified time.

- Red: Unacceptable and take immediate steps to mitigate or avoid it.

The thresholds determining shifts in how risk exposure is labeled or perceived (red, amber, green flags) reflect the level of risk tolerance at the port. The wider these thresholds, the greater the degree of tolerance. No port should take on risks with a high probability of causing death or injury, a breach of applicable laws and/or regulations or financial distress, and bankruptcy. When setting out the appropriate "risk appetite" and "risk tolerance," an agreement is needed on who will be responsible for determining risk appetite and risk tolerance, as well how to express risk appetite and risk tolerance. Figure 1 sets out the linkages between risk appetite, tolerance and capacity.

Port senior management should be responsible for setting the relevant risk appetite and risk tolerance levels which can be expressed in qualitative or quantitative terms. Examples on the qualitative side include some unpreventable operational risks, such as global pandemics and natural disasters. On the quantitative side, examples include measures related to the port’s IT system or key crane availability (e.g. set levels so that no more than a given percentage of any business-critical system or equipment becomes unavailable for more than one week in any given year).

Senior management should consider three primary factors when deciding on the port's risk appetite level:

- Port strategic objectives. For example, a port looking to grow may choose to accept a greater level of risk, taking into account health and safety and legality objectives.

- Risk preferences of key port stakeholders. Where stakeholders are more averse to risk, a lower level of risk appetite will be appropriate, and vice-versa.

- Port financial stance. Ports in a solid financial position are expected to have the funds necessary to finance the costs associated with managing risks.

The risk tolerance thresholds are established based on the agreed risk appetite. For example, red and amber thresholds need to be set for a new port IT system. Although extensive testing suggests that the system is very reliable, no historical data exists regarding the system's stability in regular daily use. Managers at the port decided to set red and amber limits based on their experience with other IT systems and user reactions to failures. Evidence suggests that a non-availability rate of less than 1 per cent is tolerable, but 2 per cent or more can significantly disrupt operations. Hence the amber threshold is set at 99 per cent availability and red at 98 per cent.

A port may communicate its overall risk appetite by using a range of methods, including staff induction and training sessions, staff meetings, intranet resources and performance reviews. It is recommended that multiple channels be used to ensure that the message is well received and understood. Risk tolerance thresholds for specific operational risks and controls should be communicated to all staff involved in the management of these risks and controls.

Procedures are required to ensure that the port remains within its chosen risk appetite and tolerance levels and uses its risk management resources most efficiently while preventing and mitigating risks. Designing and implementing these measures involve:

- Arranging for the required data on port risks to be reported by the appropriate port individual responsible for managing the risk at an agreed frequency. All reasonable steps should be taken to ensure that data is complete, accurate and timely. Risk appetite and tolerance levels should be built into existing risk reports to save time producing new reports and prevent overloading management.

- Converting data to information by adding context and interpretation (e.g. how the data compares with business performance metrics, whether the data suggests the emergence of increased or reduced risk). This entails the identification and investigation of adverse variances and trends and analyzing the underlying causes.

Figure 1: Risk appetite, risk tolerance and risk capacity.

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on various sources including the Institute of Risk management and Business Continuity Institute.