This section presents risk cases which occur due to the failure of third parties to deliver services or goods to the port.

Suppliers are the most obvious third-party dependency, but operators could also be impacted by the activities of other third parties such as governments, customers, neighbouring businesses or pressure groups. Further information about understanding and managing complex risk across an ‘extended enterprise’ can be found in the IRM’s publication ‘Risks in the Extended Enterprise’ (Institute of Risk Management, 2014).

Understanding the breadth and the depth of supplier is critical and while supplier risk entails much more than financial risks, a good example of a third-party risk is a financial failure, but other failures may affect third-party partners, customers and suppliers. Other failures may include strikes by key contractors, the closure of a supplier by government authorities, or the inability of a supplier to maintain crucial equipment.

Understanding the financial health of a third-party supplier, such as a piloting service supplier, is critical. The financial failure of third-party suppliers can be disruptive and cause operational challenges and lead to a loss of revenue. Losing an essential support service provided by a supplier can significantly hinder port operations. If a supplier or a subcontractor has substantial cash reserves, they will be better positioned to absorb the impact of a disruptive event. They are also more likely to be able to enhance their service offering and support the port’s development.

Based on their financial importance to the port, a financial assessment of existing and new suppliers or customers should be carried out. Bankruptcy predictors can be used in this respect. One of the widely used bankruptcy predictors is the Altman Z-Score.30 The Z-Score provides a well-established approach for assessing financial health and only requires a moderate level of financial data. The Z-Score combines a series of weighted ratios for public and private firms to predict the likelihood of financial insolvency. Over time the Z-Score has demonstrated almost 90 per cent accuracy in predicting bankruptcy one year in advance, and 75 per cent accuracy over two years. The Z-Score has several features that make it popular.

The Z-Score provides a numerical value related to the level of financial risk: a higher score is better than a lower score. Only four ratios are needed to calculate the Z-Score for private firms and five for public firms. The challenge with private companies is in obtaining the data to populate the model. Z-Score can be interpreted with a red, yellow and green scoring format. There are several other financial ratios and approaches that ports may want to use to assess the financial viability of third-party suppliers. They could also use international third-party service providers to help in this analysis, such as DNB, Rapid Ratings, and Creditsafe. They provide good cost-effective coverage around international public companies but more limited insight for private national companies without supplementary service activity.

Furthermore, ports could have regional financial viability service providers to support the financial analysis and help obtain relevant data. For small ports and when resources are limited, a third-party provider is likely to be the best approach.

HINT

- Backward-looking financial ratios can overlook signals of financial distress, which could be more visible when looking at qualitative measures, such as a supplier failing to meet its delivery dates required, or the declining quality of their service. A port relies on many third-party suppliers and customers.

A port should have a sound understanding of the status of all its critical third parties and suppliers/subcontractors, as any failure of any of these critical parts can significantly impact a port's operations and its business continuity and financial viability. A port cannot just make use of financial assessments that are quantitative. The best risk management approaches will feature a combination of quantitative and qualitative assessments. While ratio analysis can be a powerful tool, the technique still relies on infrequently updated historical data, challenging to obtain data, or sometimes even unreliable data.

Qualitative measures can be used to understand the status of a critical third-party supplier. Many indications of a supplier or other third-party provider’s financial situation can be seen ahead of time. The following are potential warning signs that a supplier or other third-party provider may be at risk of failure or default:

- Overly dependent on: (i) sales to a single industry or just the port itself; (ii) sales to customers in declining industries; or (iii) sales to other ports that are financially distressed or reducing operations.

- Unable to meet agreed lead times because of problems placing a purchase order for materials to its suppliers.

- Shipping early due to a lack of business.

- A key executive becomes ill, or there are significant changes in senior management.

- Significant disruptions to operations because of reduced staff availability (e.g. pandemic).

- Hints at or announces facility shutdowns, closings, and/or layoffs.

- Reduction in R&D investment, IT, equipment or resources.

- Taking more time to pay own suppliers.

- Deterioration in the quality of service.

- Suppliers offer additional discounts for timely payment, or payments are required in advance.

- Becomes subject of an investigation due to accounting irregularities.

- Rumors of problems begin to emerge around the port community or on social media.

- Loss of a substantial customer contract.

While qualitative indicators are usually not modeled quantitatively, they can still provide valuable insights. The challenge becomes one of obtaining intelligence systematically rather than receiving it on an ad-hoc basis. One way to make some qualitative assessments more systematic is to establish internet alerts that forward information about companies as soon as it enters the public domain. Qualitative techniques in assessing supplier and customer financial health can be a valuable addition to using just a historical quantitative approach.

HINT

- Consider using appropriate news alerting service providers, including those who specialize in supply chains, to provide customized news alerts on critical third parties. Having the appropriate data at hand can help the port develop the agility required to ensure the resilience of operations.

A third-party supplier audit or assessment should be conducted for critical suppliers/third-party providers before starting the contract. These audits and appraisals should be annual for existing critical suppliers or where significant concerns are raised. Audits are performed to ensure that the port supply chain members adhere to sound business and legally compliant practices. Such audits involve an objective examination and evaluation by a port of a supplier's performance and practices to ensure they align with relevant requirements, including those relating to ethics, regulations, laws, business continuity and standards. For ports, this would include relevant freight forwarders and transport partners.

Audits of suppliers or third-party providers traditionally focus on costs, quality and delivery. More and more, these audits need to consider suppliers' commitment to standards and legal requirements related to ethics, labour practices, health and safety, environment, as well as cyber and data security. In addition, these audits need to consider whether supplier shave business continuity and emergency plans in place and whether these plans address port risk scenarios.

In addition, it is also useful to have their business continuity and contingency plans, if any, and whether they address port risk scenarios and environmental concerns. The auditor, either as a port employee or a third-party designated by the port, understands that supplier issues place the port at risk from various perspectives, including reputational risk. Some supplier audits focus on topics beyond the scope of supplier performance scorecards, such as a supplier's adherence to social and regulatory requirements, for example, in respect of fair labour and environmental practices.

It is difficult to have any standard port template for supplier audits because ports often have different reasons for performing the audit and are likely to have additional legal and regulatory requirements. However, a framework can be created and be tailored to meet the port’s requirements.

HINT

- Ensure that the underlying contracts for relevant suppliers and third-party providers give the port access to relevant data and personnel, and allow audits or ongoing assessments to be performed.

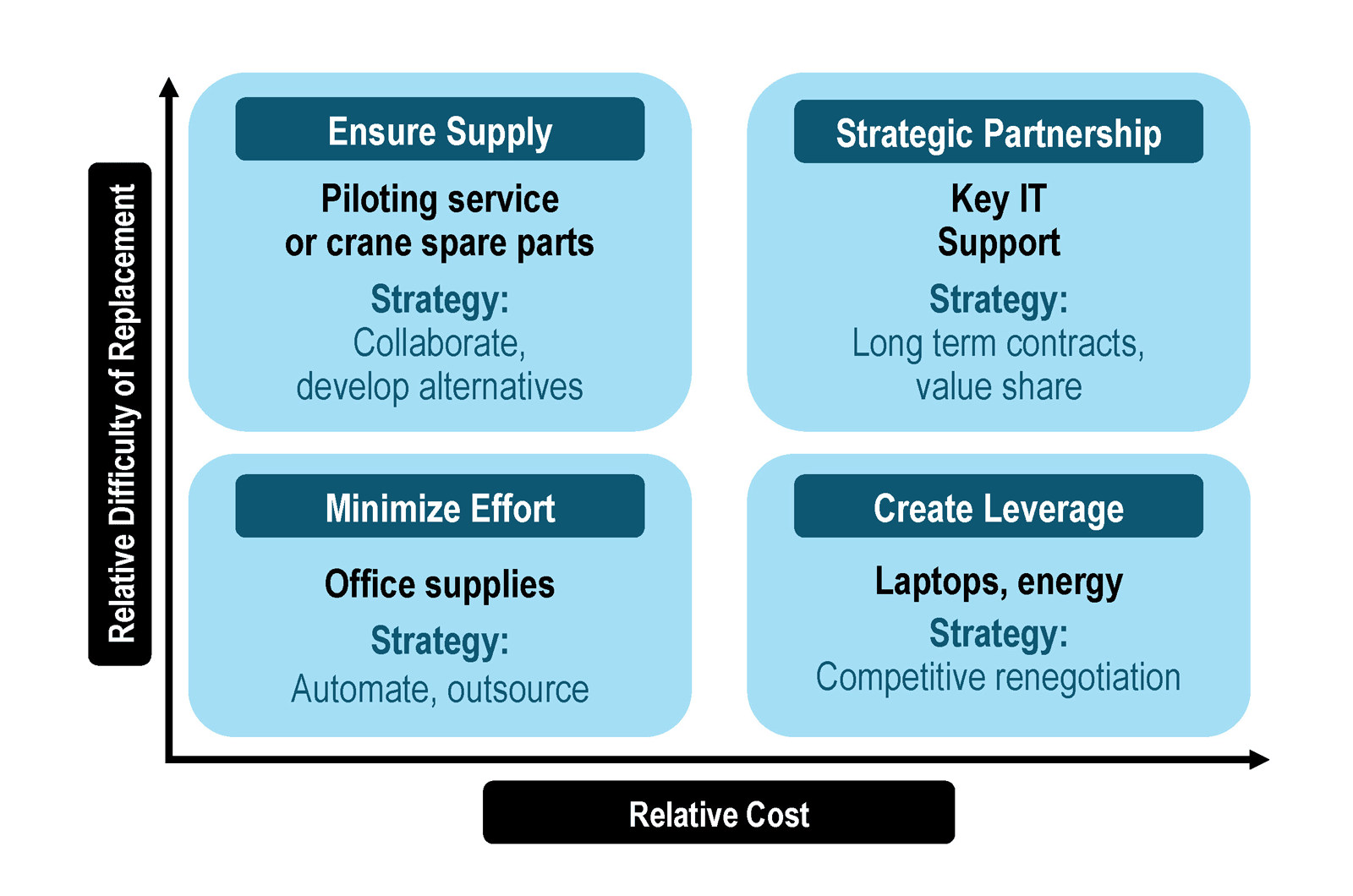

Ports must understand the extent of their reliance on suppliers and third-party providers. An important part of supplier management involves the development of appropriate supplier strategies. A failure to develop strategies presents a severe risk to effective port resilience. A tool called the portfolio matrix (Kraljic) (Figure 7) is one that port staff managing suppliers should understand and routinely apply when developing supply and supplier strategies.

Poorly developed supplier/supply chain strategies create a wide array of risks – the portfolio matrix is designed to ensure this is not the case. Using the supplier portfolio matrix as a positioning tool helps: (i) identify the type of supplier relationship to pursue; (ii) whether to engage in a win-lose or win-win negotiation and relationship; (iii) whether to take a price or cost analytic approach when managing the commodity or item; (iv) the types of supply strategies and approaches that should work best; (v) how to measure supplier performance including the port risk exposure; and (vi) how best to create value across different purchase requirements.

Figure 7: Supplier and third-party portfolio matrix

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on various sources including the Institute of Risk management and Business Continuity Institute.

The matrix segments the purchases and supplies from third parties across two dimensions articulated around risks and impact. Risk (Y-axis) captures the number of active suppliers in the marketplace (such as suppliers of port equipment like cranes or vessel scheduling IT solutions) that provide services or the relevant product/components to the port. Impact (X-axis) features the cost or value of the good or the service to the port. A supplier manager quantifies how much the port spends for a category of product or service (i.e. the value at risk to the port from the failure of this category). The product or service is sourced from a supplier will be positioned within the most appropriate area of the portfolio matrix. Depending on where the supplier stands in the matrix layout, four situations can result, calling for different responses and strategies by the port, including:

- Minimize effort/transaction: The goods and services have a low total value and impact. Reducing the transaction cost of a purchase is the primary way for the port to create value, usually through electronic purchasing systems. Even when a requirement has many possible suppliers, the cost of comparing these options outweighs the value of searching for suppliers. Any price or risk analysis is cursory due to the low value of the good or service and the limited impact they would have on the port if they failed. As per the diagram, this would include office paper and other stationery supplies for the port.

- Create leverage/market quadrant: Items purchases include standard items or services with lower to total medium value. Many suppliers can provide substitutable products and services, and hence limited disruption impact on the port, well-defined specifications and lower supplier switching costs. The port should rely on market forces to determine the most efficient service provider or producer. When obtaining these services or items, competitive bidding or price comparisons, spot buys, shorter-term contracting, and reverse auctions are often used. Relationships with the providers of market items are typically competitive (i.e. win-lose) and price-focused. Ports should use the power of the marketplace to have suppliers actively compete for their business.

- Ensure supply or bottleneck: This situation includes services and purchase items, which, although not very costly, would create a significant impact on the port's operations if they stop being available (e.g. smaller spare parts for critical port equipment). The port needs to focus on ensuring the relevant good or service supply.

- Strategic partnership/critical situation: This includes goods and services that have high costs or value impact and are essential to a port's operation. This situation also features fewer suppliers that can satisfy a port's requirements, which often involves customization rather than standardization. The port creates value when managing necessary items and services by pursuing collaborative and alliance-type relationships with suppliers/third parties, e.g. piloting services or ship to shore cranes. Items that are critical with relatively few suppliers also mean suppliers have significant power. Using a portfolio risk approach helps ensure that the port strategies concerning its supplies and risk requirements are aligned. An example would be the piloting services or specialist dredging operations, where the availability of alternative suppliers is limited. Still, the failure of the process could have a significant impact on the port.

A useful strategy in supplier management involves the development of commodity or category strategies. A category is a logical group of related items or services from a supply market sector where suppliers operate in a similar supply chain. e.g. the supply of piloting services in the port. A category is named after the item or service provided and not the names of the supply companies involved. A category that accounts for more than 5 per cent of the total supply spend is probably too large and should be divided into two or smaller groups, e.g. IT would be too big a category on its own, either because its supply chains go back to different sources (hardware manufacturers or software engineers), or because total IT expenditure exceeds the 5 per cent threshold. Examples of categories might include ship-to-shore cranes, temporary labour services, and IT service providers. Commodity or category sourcing teams should include commodity or category risk assessment plans in their purchase strategy development process. This forces ports to assume the responsibility for risk management rather than shifting it to another party. It also helps embed risk management thinking into the corporate culture.

A commodity or category risk plan may include the following sections:

- Market analysis involves an intelligence report that describes the supply market for the commodity/material. It asks: (i) who are the major suppliers, and where are they located?; (ii) who are the primary customers?; (iii) what are the supply trends?; (iv) are there specific supply and demand price drivers?; (v) what is the overall competitive environment of the market for this commodity?; and (vi) what is the available market capacity relevant to my location?

- Risk identification involves identifying and categorizing risk(s), including a detailed description of each risk (i.e. not a generalization, such as 'potential supply disruption' or 'bad weather, but that this critical supplier's leading production site is in a flood risk zone).

- Risk scenario mapping requires the development of a risk scenario map with each risk plotted on the map.

- Risk management plans involve a comprehensive risk management plan that identifies actions on how to mitigate or manage the risks identified in the previous step. It should also include a timeline that shows how and when to carry out risk management actions.

- Risk resources involves a listing of objective references and information sources on the demand and supply market for that commodity. It should identify why each information source is valuable. Emphasis should be given to sources that are updated regularly.

Multiple supply sources can help mitigate and manage third-party supplier risks. Every additional supplier brings: (i) additional negotiating and contracting costs; (ii) material, informational and financial transaction costs; (iii) relationship management costs; (iv) measurement costs; (v) logistical costs; (vi) possibly higher prices as purchase volumes are divided among multiple suppliers; (vii) supply chain complexity costs; and (viii) costs resulting from increased supply chain variability. However, there is a benefit in diversifying port suppliers since they can help the port recover faster from disruption, or other risk events, due to additional sources of supply. This is a benefit that would outweigh the costs. For example, the supply of piloting services or relevant port equipment spare parts.

The disadvantages of single sourcing suppliers include the increased difficulty of moving to a new supplier, given prior performance issues or the rise of disruption, loss of competition, potential over-dependence of port on a particular supplier and vice versa, and general capacity issues.

When faced with supply chain risk or uncertainty, another approach consists of holding a buffer or safety stock at the port or at a convenient local storage facility. Safety stock, also called buffer stock, is the level of extra stock that is maintained to mitigate risk due to uncertainties or events affecting either the demand or supply side of port operations. Good reasons exist for considering the use of buffer, or safety stock, at a port; reasons include: (i) protecting against unforeseen variation in supply, perhaps due to supplier quality problems; (ii) compensating for forecast inaccuracies when demand exceeds supply; and (iii) preventing disruptions in port operations.

At the same time, deciding to increase buffer or safety stock has direct port operational and financial implications. On the financial side, safety stock results in greater inventory, which raises a port's current assets and has associated carrying costs (e.g. interest, obsolescence and warehouse space). On the operational side, a port that increases safety stock realizes all the supply chain-related costs related to planning, sourcing and holding a product. The only difference is that the inventory is held 'just in case' and, until used, creates only costs rather than revenue. An example where it might be appropriate for a port to carry buffer stock is to hold spares for key pieces of port equipment, e.g. cranes or other moving equipment.

Contracting is a powerful way for ports and relevant third parties to address and manage risk in an explicit manner. One way to ensure that contracts do not unintentionally create risk is by doing business with companies located in countries that have signed the United Nations Convention on the Internal Sale of Goods (CISG). The CISG is a multilateral treaty that establishes a uniform framework governing international commerce. Ratified by over 90 countries, the convention applies to a significant portion of world trade.

Parties to a contract can negotiate or agree to price but also some of the following items:

- Quality, delivery, and cycle time expectations;

- Technical support;

- Joint improvement activities and contracting management process;

- Extended warranties;

- Additional services provided by suppliers;

- Problem resolution mechanisms;

- Investment and resource commitments committed to by the parties;

- Volume commitments;

- Guarantees of supply over changing demand conditions;

- Non-performance penalties and continuous improvement incentives;

- Agreement on allowable costs;

- Risk and reward sharing, including business continuity;

- Agreement on exit clauses;

- Protection of intellectual property; and

- The management of currencies and insurance.

It is also important to have an appropriate contracting or supplier management process, particularly in respect of critical port suppliers/third parties. Contracting management practices a port may wish to consider include:

- Involving the port's internal customers during contract development. Most contracts aim to support the needs of internal participants. Involving them will ensure the quality management principle of understanding customers and their requirements.

- Entering into agreements with world-class companies and individuals. This recognizes the importance of supplier and customer selection as a core business process, with appropriate financial due diligence and referencing of third parties and key management team members.

- Ensuring complete contracts to ensure that parties' obligations are well specified in the contract. This reduces the risk of contract failure and the costs of monitoring the contract relationship.

- Obtaining contract performance feedback from internal port customers. They should be regularly surveyed about their satisfaction in areas directly related to a contract, including changes in respect of third parties that may indicate risk issues.

- Assigning a relationship manager to major port contracts with performance accountability. A highly used organizational design feature involves assigning specific individuals to manage supplier relationships, including their approach to risk management.

- Measuring and reporting internal customer and site compliance to port-wide agreements. An issue that can expose a port to risk is the failure to follow through on committed contractual items, particularly using a supplier that has not been approved through regular processes, or which could impact overall port purchase volumes.

- Ensuring a system is in place to compares prices paid against contracted prices to ensure compliance with negotiated prices and avoid creating financial risks.

- Measuring real-time supply chain performance and service levels. Real-time data supports the objective measurement and management of supply chain contracts. This is increasingly becoming available in ports in line with the digitization of supply chains.

- Conducting periodic contract performance review meetings. Regular contract review meetings should be the responsibility of relationship managers; these review meetings should include appropriate updates on risk management. The relationship manager should also conduct regular review sessions with internal customers to gain feedback on a contract and its performance.

- Using contract management systems and systems technology. Ports can use third-party contract management software (CMS) applications, where appropriate. A good practice is to have a contracts database to understand the current contractual commitments.

- Benchmarking contract management practices against other ports or commercial organizations. Ports should routinely benchmark their contract management practices against leading firms or industry contacts. Professional bodies, such as the Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply, offer training and advice.