Geopolitical events, particularly conflicts, represent acute disruptions for the ports involved. As a result of conflicts, port infrastructure can be damaged, pillaged and unmaintained; this would undermine its capacity to support basic demand for essential goods. A facility could become inoperable because of security considerations for the cargo and the workforce. Managers and workers could have fled and shipping lines could refuse to call on a facility. Following the Arab Spring of 2011, several countries in North Africa and the Middle East faced social turmoil and, in some cases, degenerated into civil war. Port activity in Libyan ports (Tripoli and Benghazi), Syria (Tartus, Latakia) and Yemen (Aden) has collapsed and barely recovered since then. In the case of civil unrest, ports can become the focus of relief efforts where international aid arrives, which creates a unique set of challenges as populations converge towards port facilities.

Economic embargos can equally have adverse effects on port activity in both the country subject to sanctions and the ports of its trade partners. Iranian ports have been impacted by successive waves of sanctions set in the wake of the Iranian Revolution in 1979. The case of Venezuela is also illustrative as economic policy and associated massive decline in economic activity since 2015 have undermined port volumes, as occurred in the leading national ports of Puerto Cabello and La Guaira. In 2022, the Russian invasion of Ukraine resulted in international sanctions curtailing its port activities, and several strategic resources, such as energy (petroleum and natural gas), fertilizers and wheat.

Box 2: Conflict in the Black Sea

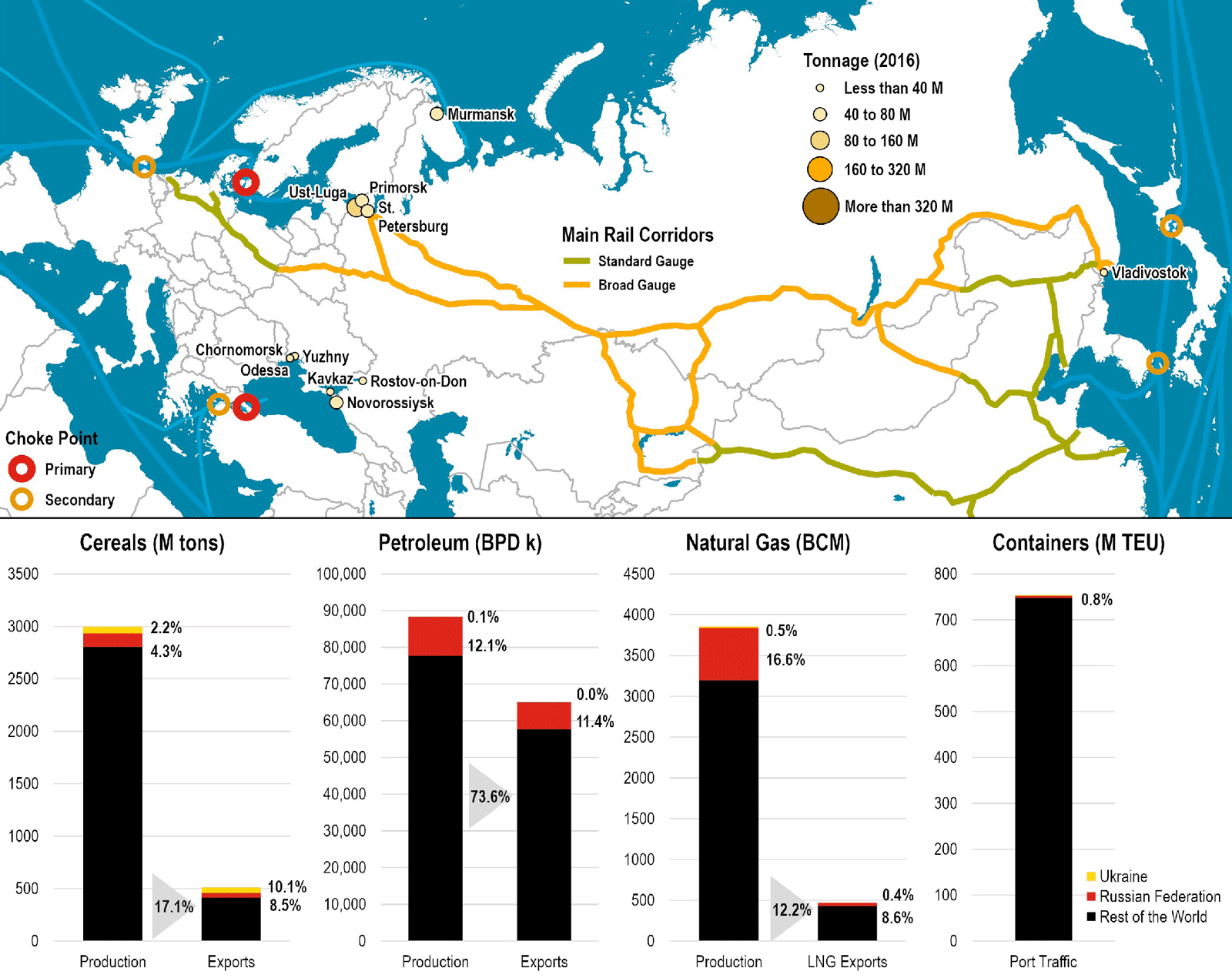

The Russian Federation-Ukraine conflict has further exposed the vulnerability of the global maritime supply chain to shocks and disruptions. While Russia and Ukraine account for relatively small shares of world trade and output, they are important suppliers of food and energy, among other inputs, into industrial value chains (figure 31). The conflict has complex and difficult to predict ramifications on global supply chains, as it is often only possible to determine which supply chains had been the most impacted after the event.

Figure 31: Russian Federation and Ukraine - Transport networks and contribution to global trade

Source: Based on data from FAO, the BP Statistical Review of World Energy July 2021, and J.P. Rodrigue, Global Container Port Database.

Maritime grains export from Ukraine dipped by 95 per cent in March 2022, while exports from Russia declined by over 10 per cent. Major grain importers have been trying to secure alternative sources, which involves new import routes. For example, while Egypt’s maritime grain imports from Ukraine slumped by 97 per cent between February and March 2022, their imports from the United States increased by over nine times during this period.3 This can have an impact on both the deployment of bulk ships and the capacity of the shipping industry to handle these sudden shifts. Existing grain supplies from Ukraine could not be exported as the country’s ports are closed due to the war. Vessel calls at Ukrainian ports fell by more than 90 per cent immediately after the start of the war. A 20 per cent fall was recorded in vessel calls at Russian ports. Already expensive and over-stretched maritime trade will find it difficult to substitute for the unviable land and air routes. In 2021, 1.5 million ocean containers of cargo were shipped by rail west from China to Europe. If volumes currently using the container rail would be added to the Asia-Europe ocean freight demand this would mean an increase in an already congested trade. The implications for freight rates are significant due to higher fuel costs, re-routing efforts and limited capacity in maritime logistics. By raising food and fuel prices, the conflict is already accelerating inflation in many countries, with adverse distributional impacts among the poorest segments of populations who tend to spend a disproportionately high share of their income on food and energy. At the same time, fuel and food-import dependent countries will experience deteriorations in their balance of payments and exchange rate pressure.

Source: UNCTAD (2022).